At Seven Hills, students can often face challenges that impact their mental, emotional, and physical well-being. These obstacles can stem from social dynamics, which play a significant role in shaping student experiences. The social environment at Seven Hills while supportive in ways can also present obstacles that affect a student’s involvement in their academic life. The school’s wellness program is designed to provide a safe environment for all students so they can connect with peers who share similar struggles. However, not everyone feels they have equal opportunities to benefit from the groups.

The wellness groups are intended to offer a safe space where students can connect with peers who share similar struggles. However, not every student feels they have equal opportunities to benefit from these groups.

For some students, wellness groups can offer a sense of community and belonging that they might not find anywhere else. For those like junior George Mullin, the wellness groups proved to be a special source of support and connection. “I have other people in the world who also have ADHD and that also go through the same things that I do,” he said, describing the comfort some of these meetings have given him. The shared experiences in these spaces allow students to build stronger relationships and feel less isolated. In many ways, the groups provide a sense of belonging that may be difficult to find in other school areas.

However, not all students share the same positive experiences. The wellness groups can feel limited to students who feel these groups are irrelevant to their own needs. Mullin himself pointed out, “I think the wellness groups create more division in our school more than anything.” Instead of fostering collaboration, these groups can unintentionally reinforce boundaries between students who may have different needs or struggles. The groups, rather than integrating students with a wide range of experiences, can make them feel even more separated from their peers.

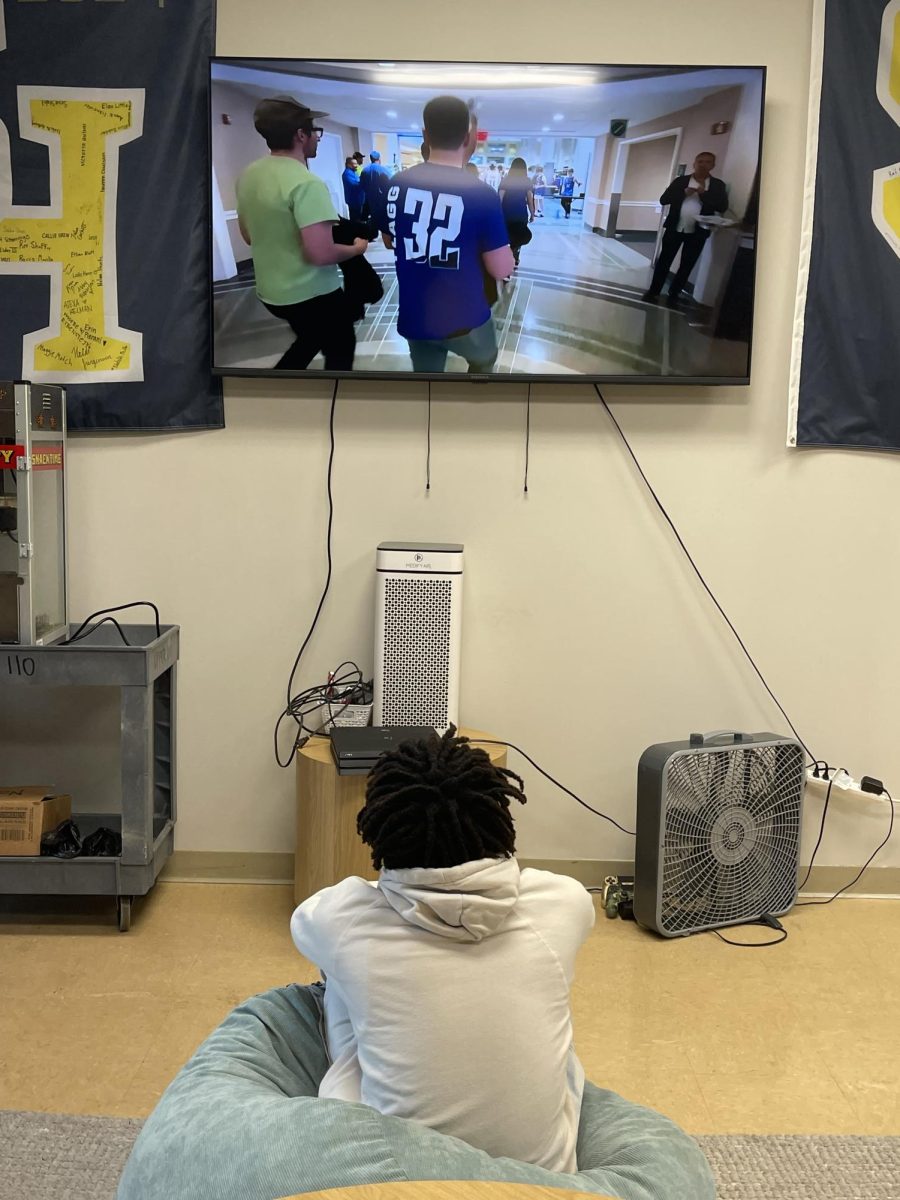

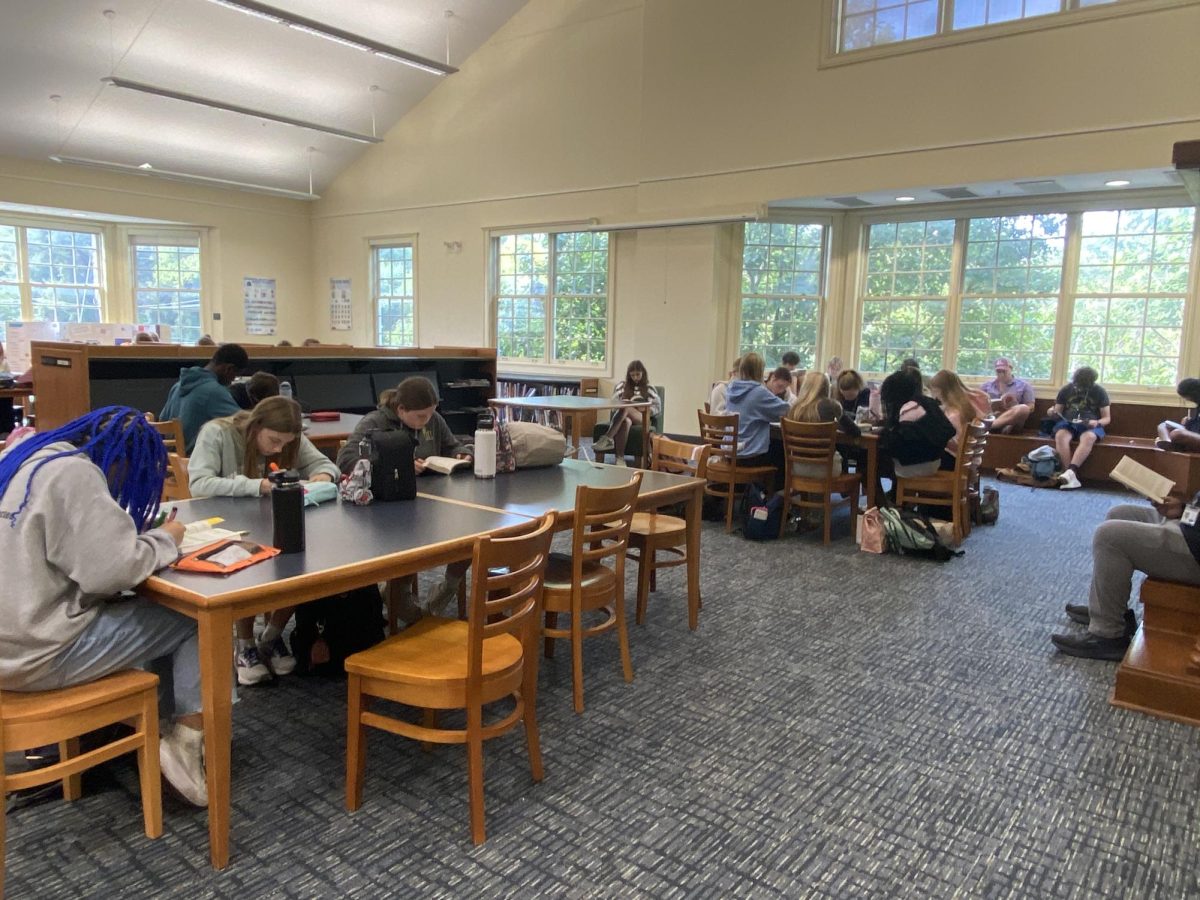

Junior Brendan McLaughlin offers a different perspective, describing how wellness groups have helped him form stronger relationships with other students who share similar challenges. “I feel more connected to those people.” Though McLaughlin generally enjoys the wellness groups, he raises an important concern: “If there are other students who aren’t part of one or don’t want to join one, you’re forced to go to the library and read.” This leaves those who don’t connect with any particular group feeling sidelined. The program, rather than offering an inclusive solution for all students, can actually force many into a passive alternative that doesn’t necessarily address their own emotional needs.

The library, as an alternative, presents another problem. For students who feel disconnected from the wellness groups, the library is often the only option available. While this might seem like a simple solution, it can highlight a larger issue: a lack of meaningful engagement and support for those who don’t fit into the wellness group model. Furthermore, the frequent changes in library rules can add to students’ frustration, making it harder to find stability or a sense of belonging in their school environment. This shows a lack of meaningful engagement and support for those who don’t fit into the wellness group mold. The constant changes to the library rules only add to the frustration, making it harder for students to find stability or a sense of belonging in their school environment.

Despite these challenges, there is widespread agreement among students and faculty that the conversation about mental health and wellness is crucial. As McLaughlin noted, “It’s equally important to make sure no one feels left out.” At the end of the day, wellness is about connection. If the current program unintentionally creates more barriers than it breaks down, it’s worth considering ways to improve it.

Ethan Hu • Dec 13, 2024 at 9:28 am

As a minority, I simply cannot comprehend the necessity of distinguishing people based on their race. We are not inherently inferior to any other racial group nor are we more vulnerable. I don’t want to be treated as infants when white people do not. I take pride in my culture, and this pride is not fueled by external recognition.