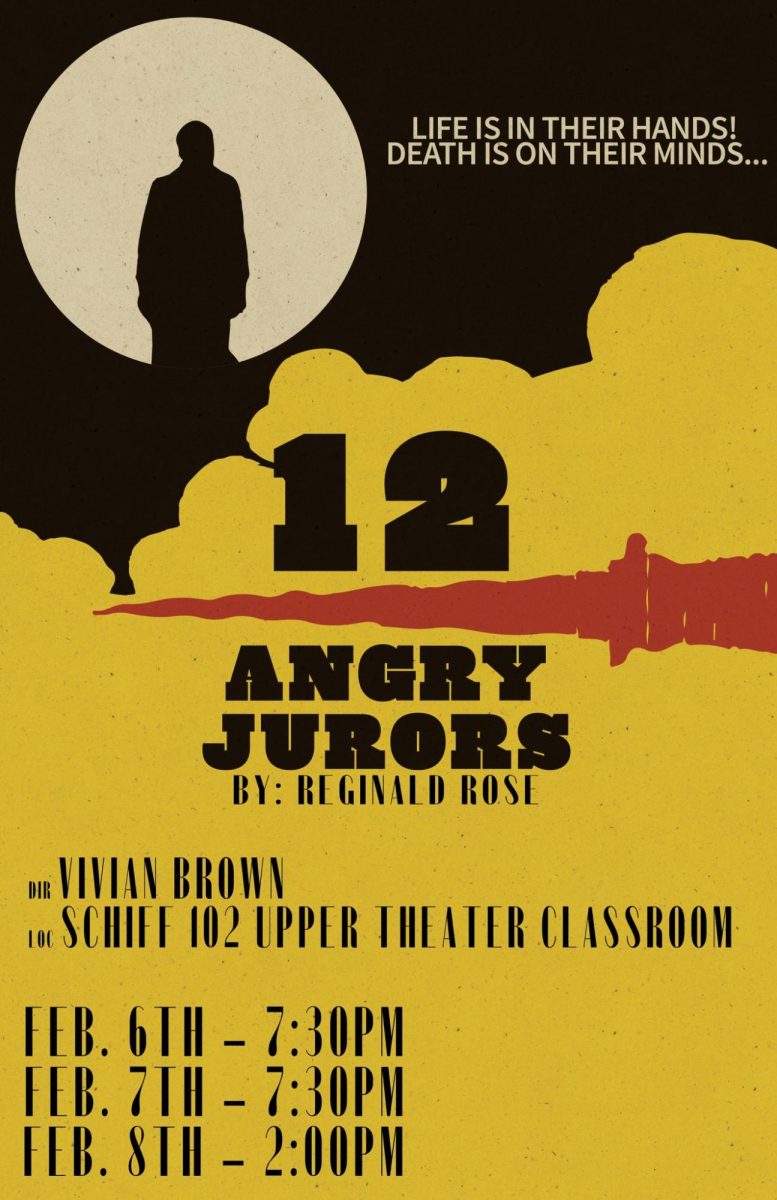

Behind the scenes in the Schiff Center, James Earl Tatum III, also known as Trey Tatum, works to create the school’s plays and

musicals. Out of all the members of the school community, Tatum is the most mysterious because he likes to stay out of the spotlight. From his lack of an advisory, to his “hidden” office backstage in the Schiff Center, many students wonder what he does on campus. Tatum was born in Gulf Shores, Alabama, and has been a part of the theater community for the better part of 30 years. From building sets to running the after school technical theater program for school productions, Tatum’s role is far from ordinary—just like the path that brought him here.

The interview with Tatum took place in his office in the back of the Schiff Center. He has transformed his office into a tiki bar-inspired collection of tropical decorations and kitschy, playful nicknacks. Woven grass, palm fronds, and bamboo wallpaper decorate his fish tank, vintage lamps, and walls. I followed him to the Tech Theater classroom where we started the interview. Colorful, painted chairs sit in front of the iMacs used to record the podcasts that Tatum and his students create during class. Tatum laid down on a rug, bought for his son, and did stretches during the interview because his hip felt sprained.

From a young age, theater has always been a part of Tatum’s life. Tatum’s introduction to theater was through his childhood best friend’s mom, Karen Cater, living in Alabama. She was an after-school theater teacher, much in the same way Tatum is, and she also participated in community theater. Tatum recalls Cater as a positive and eclectic influence on his life, setting the benchmark for how he approaches theater and teaching. Cater would take her son, Reid, and Tatum on what she called “Adventure Days.” where she would drive them to random places. One day, Cater drove Tatum and Reid to a random house, hopped the fence, and climbed up on the slide leading toward a backyard pool. Tatum trusted that Cater had taken them to a house that was empty or for sale, but sure enough, the house was home to a whole family that was eating dinner while Tatum, Reid, and Cater swam in their pool.

Cater, using money given by the city, created an after-school theater program for children. Tatum remembers the immense impact that this program had on him. The program was fun and silly, but also taught Tatum the feeling of being proud of something he had worked hard on. Tatum tries to channel her energy into his teaching. This sense of spontaneity and fun appears in Tatum’s teaching methods and after-school programs: he lets kids take the reins, experiment, and, most of all, be kids.

“I’m trying to make a place that felt like what that felt like to me as a kid,” Tatum said. He expects his students to work and play equally, working hard and goofing off. For him, the after-school space is a sacred place for kids to socialize, work, and have fun—an area where kids can blow off steam from school and focus on creating art.

After graduating from Birmingham-Southern University with a degree in Theater Arts, Tatum had a stint in Nashville before moving to New York City to pursue his theater career. He ended up running a non-profit theater in Times Square called the Tank. In New York City, he met his wife, and they married in 2013. Soon after marrying, Leak, an accomplished director herself, got a job as a directing fellow at the Cincinnati Playhouse in the Park. They planned to spend the year apart with Leak working at the Playhouse and Tatum moving in with their downstairs neighbor in New York City to save money for their savings and vacation. Their neighbor was named Ursula, and she lived with her daughter, Nell, in a two-bedroom apartment as a single mother. Ursula and her daughter slept in the same room, so Tatum took residence in Nell’s former bedroom. But two weeks before Leak was supposed to leave for Cincinnati, Tatum felt that this was not how he wanted to spend their first year of marriage, so they moved together to Cincinnati.

For the first six months of living in Cincinnati, Tatum and Leak were on heat assistance and food stamps because Leak was a teaching artist at the Playhouse, and Tatum was working as a freelance playwright and audio editor. At a party, Tatum and Leak ran into a friend of theirs working as the theater teacher of Milford High School. She told Tatum aboutan opening for a technical theater director at Milford.

The next day, having forgotten which high school she worked at, Tatum browsed the internet for part-time technical theater teaching jobs where he found an opening at Seven Hills. “How many high schools in Cincinnati can be looking for a tech director right now,” Tatum said. He applied, Tina Kuhlman called, they had an interview, and Tatum got the job. His friend at Milford called and asked why he never applied, and Trey responded, “What are you talking about? I just accepted the job.” The hours and the pay were better at Seven Hills, so Tatum stayed here, where he’s been for the past ten years.

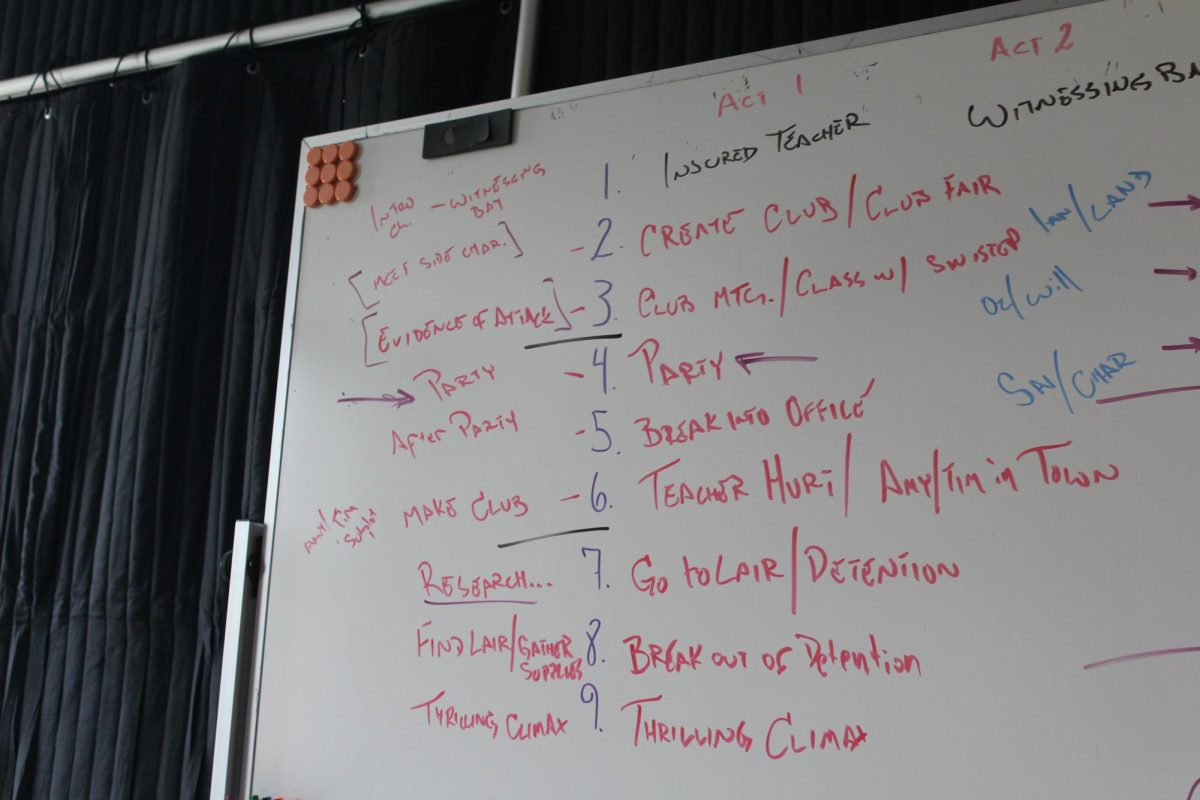

The question still remains: “What does Trey Tatum do?” He is the director of the technical aspect of the Theater department, working the backstage by building sets, helping to run the lights and sound, and moving sets on and off stage during performances. But that is not Tatum’s true specialty. His degree is in Theater Arts—the backstage portion is only one part of what he does. In more general terms, Tatum is a storyteller. Whether writing plays, audio drama podcasts, or short anecdotes, Tatum tells stories. His job here, at Seven Hills, is to tell and make stories with his students and teach them something along the way.

Oz Knarr • Oct 9, 2024 at 2:13 pm

This was soooo cute!!