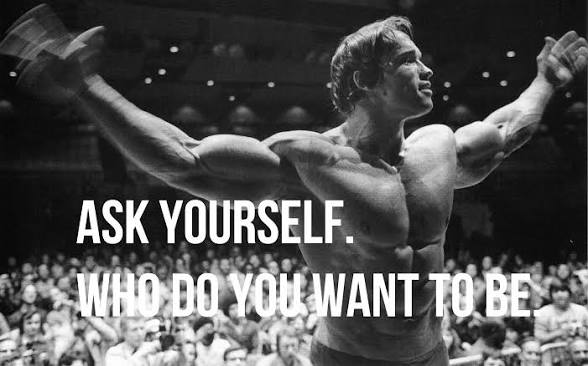

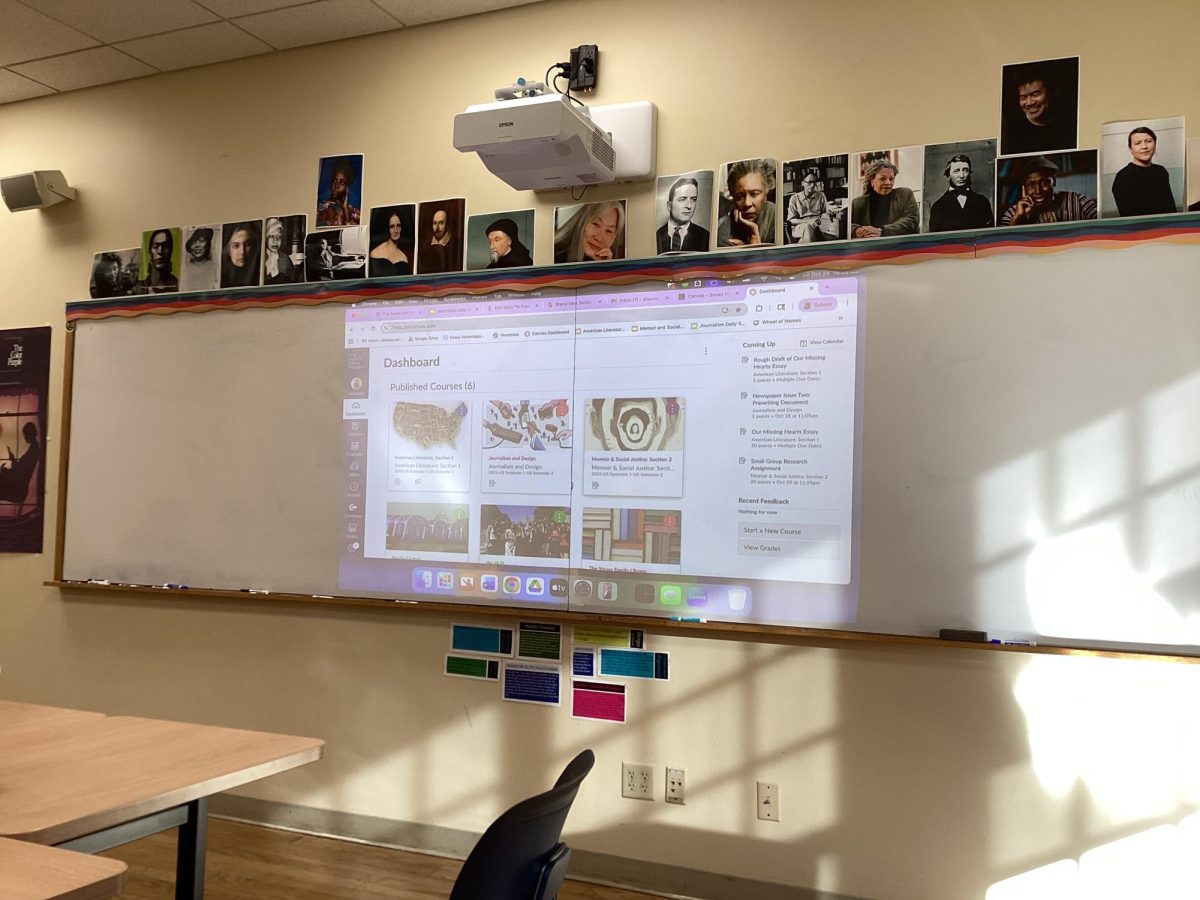

If you’ve walked through the halls of Seven Hills recently, you’ve probably noticed the new posters that line the walls. Some are in English, some in black and white, and some are in foreign languages. They feature short, bold messages and striking images, serving as reminders of hard work and purpose.

The source behind them? Dean of Students, Dan Polifka.

At first glance, these posters might look like typical school decor, simply just motivational messages meant to inspire students. But for Polifka, they stand for something deeper. This instead idea started with a revelation.

Polifka stated that, “A colleague gave a speech at the start of the year,” he said. “She pointed out that schools always ask, ‘What do you want to do?’ But the better question is, ‘Who do you want to be?”

That distinction, between doing and being, captures what the posters are trying to hint at. Polifka mentions that “taglines stick,” which captures his idea that the posters are not meant to advertise achievement, but to plant questions. Still, not all of the students see them that way.

For many students, the posters blend into the busy nature of the hallway. One student, who preferred to stay anonymous, said she noticed them but did not feel a personal connection to them.“Yeah, I’ve seen them,” she said. “I thought maybe Dr. Carlson put them up. They just look like motivational pictures someone found online.” To her, the issue isn’t the message, but instead the thought process and selection behind the posters. “If I had the choice, I’d replace them with paintings or something more calming,” she said. This comment reflects a common tension in the school environment, which is how to find the balance between meaningful messages with the visual and emotional tone of the surrounding environment. Inspiration can not just be read; it also has to provoke meaning.

Junior Campbell Coyne has a softer take on this new change.

“I’ve read a few of them,” Coyne said. “Mostly because I was in Mr. Polifka’s advisory. But I haven’t read them all, because some of them are hard to understand.”

Still, she supports the idea of having meaningful messages in the form of posters. Coyne would like to keep them up, but “maybe move them to places where people slow down.” Her suggestion points to another issue: attention. Inspiration might require not just the right message, but also the right location. A fast-paced moving hallway might not be where reflection takes action.

Despite mixed reactions, Polifka seems content with the project’s uncertainty. These posters are meant to spark thought, not solidify it.

Polifka leaves students with one final message: “They’ll come down eventually, but however long they’re up, I hope they’re inspirational, and that they encourage students to ask life’s biggest question.”

Polifka is also open to involving students in the process of choosing or illustrating posters, which is an idea that could bridge the gap between intent and impact. If the posters began as a question posed to students, the next step might be letting the students respond.

Whether students read them closely or not, the posters make a statement about the school’s culture. They reflect a place that wants students to think outside of traditional ideas, and to take a brief moment to reflect.

Still, the mixed questions about how schools inspire raise a question: Can inspiration be designed, or does it have to come from conversation, experience, and communication?

The posters don’t demand answers, just a moment of thought:

Who do you want to be?